Some folk have said that these giants are an anomaly. And that the Professor discarded their existence entirely for the more serious mythology. Tom Shippey has even gone as far as to suggest they were contemplated as allegorical weather phenomena - and that “the passage is a failure of tone” (The Road to Middle-earth, pg. 76).

The three most recognized scholars who have concentrated effort on The Hobbit: John Rateliff, Douglas Anderson and Mark Atherton - have nothing concrete to point to either. A large form of Troll, or The gnome Rubezahl in Andrew Lang’s The Brown Fairy Book, or Fenja and Menja - giantesses from The Song of Grotti - as antecedents - are all too far removed and stretch the imagination, I deem. Moreover there is little help available from Robert Foster in his The Complete Guide to Middle-earth, or what’s available in The Encyclopedia of Arda or even The Tolkien Gateway.

Everybody seems to be at a loss.

The main problem seems to be that in 85+ years no one has yet come across a viable source Tolkien might well have used. If we could discover an applicable mythology - it would wholly eliminate doubt in the minds of many - I’m sure. That is, of course, if the match is strong. So, given a lack of ‘decent evidence’, some folk have come to believe that the origin of the stone-giants lies mainly with Tolkien himself. Just like the ents - they were sort of ‘invented’ through his sub-creative skills.

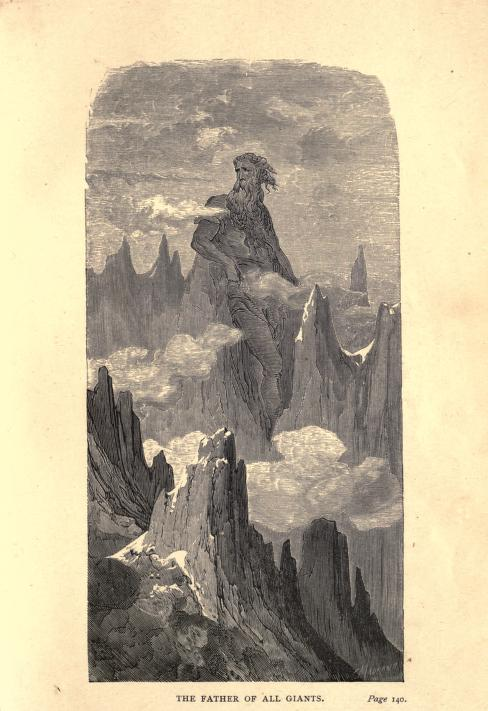

But that is almost certainly not the truth - for there definitely exists a literary provenance. Indeed - an extremely good root. And it is a testament to Tolkien’s knowledge that he was aware (I’m sure) of a fairy tale set in the mountains of the Alps involving colossal giants - whereas I’m guessing tens of thousands of studious scholars (and maybe even more) have failed to run across it.

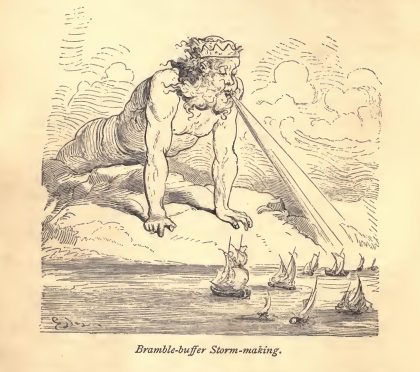

The story I believe from which the stone-giants were ‘extracted’ was written by one of Tolkien’s favored authors - Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen. It is the tale of The Giant Bramble-Buffer from River Legends, 1875.

The stone-giants are only mentioned briefly in The Hobbit. But what characteristics they do exhibit/display, match up splendidly with the River Legends account. A cursory comparative review right away tells us this was likely Tolkien’s source:

From The Hobbit, Chapter IV:

“… the stone-giants were out, and were hurling rocks at one another for a game, and catching them, and tossing them … They could hear the giants guffawing and shouting all over the mountainsides. … ‘… we shall be picked up by some giant and kicked sky-high for a football.’ ”. (my underlined emphasis)

From River Legends:

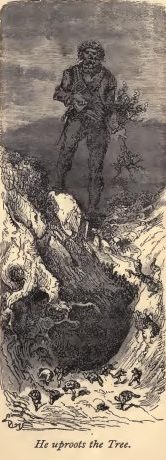

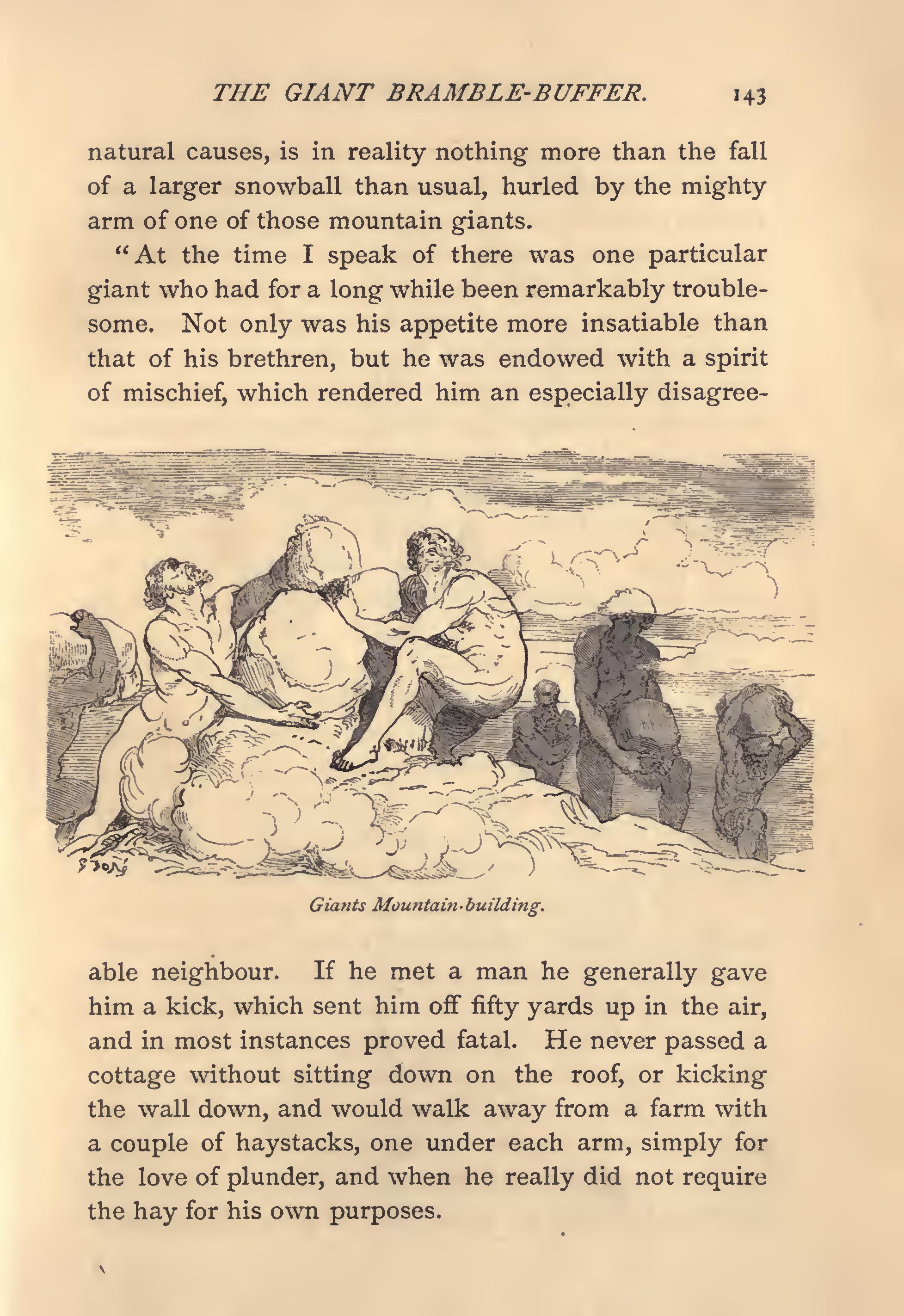

The mountain inhabiting giants of interest would:

“ ‘… fling enormous stones at each other in sport, which was pastime anything but delightful to their neighbours, whose lives and property were thereby grievously imperilled. …’ ”. (my underlined emphasis)

They were described as highly vocal ‘Daddyroarers’:

“ ‘…‘roarer’ is … intended to convey, … the gruff and deep-toned voice which usually characterizes the giant …’ … ‘… roaming far and wide over the mountains … loud cries and roars were often heard for miles, …’ ”. (my underlined emphasis)

While one particular giant, Bramble-Buffer:

“ ‘… if he met a man he generally gave him a kick, which sent him off fifty yards up in the air, and in most instances proved fatal. …’ ”. (my underlined emphasis)

Hmm .... undoubtedly then, the Professor’s children’s story had a sturdy mythological framework. As such - it only makes me admire it even more!

More to come .....